Author's note: This writing is part of my Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies, and Conflict Free Diamonds—a 45,000 word investigation into the dark underbelly of the jewelry industry organized by the metaphor of layered Russian nesting dolls. This section explores how the notion of a “conflict free diamond” is finessed by ethical jewelers to create a new diamond story, reinforcing the Kimberley Process narrative while denouncing the process itself.

—Marc Choyt

[Since I first published this piece, I have decided to call for a Boycott of Conflict Free Diamonds. Read here why I believe we should abandon this racist term.]

The pressure was really on the ethical jewelry community when Global Witness dropped out of the Kimberley Process, stating that its decision to accept Zimbabwe diamonds had “turned an international conflict prevention mechanism into a cynical corporate accreditation scheme.”

Ethical jewelers had to do something about the Zimbabwe diamonds for their more “sophisticated” consumers, including the internet-savvy millennials who were concerned about ethically-sourced diamonds.

Here, pioneer ethical jewelers made a collective choice. The Kimberley Process was no longer credible—yet the conflict free narrative was fully embedded in the public, and had to be used to sell diamonds.

This is the critical point: pioneer ethical jewelers began to finesse and spin the term “conflict free.”

First, they differentiate their market position from mainstream jewelers.

Look on a jeweler’s website who claims to be exceptionally ethical, and you’ll see that they fully acknowledge the Kimberley Process is a weak system. If they have just a little knowledge about diamond sourcing, they will explain how “conflict free” only applies to conflicts perpetrated by rebel movements—allowing for blood diamonds, such as those mined in Zimbabwe, to filter through.

Virtually all of them convey that the Kimberley Process does not address human rights, labor, or environmental issues.

Perhaps the most sophisticated marketing response is from Brilliant Earth, who have trademarked their “Beyond” narrative, backed by some of the most comprehensive articles on diamond sourcing issues available.

Screenshot from summer 2018.

In using this tactic, the validity of the Kimberley Process framework is affirmed—because even as jewelers denounce it, they embrace and validate its consumer-facing language: conflict free.

[Read more about Brilliant Earth in the Eighth Russian Doll, the next section of the Exposé.]

Essentially, you embrace a narrative invented as a cover-up for wars funded by diamonds that killed millions of people because it’s what the public understands.

Guilt free and conflict free. Don’t worry, be happy.

Spinning “Conflict Free” Diamonds

The past is deflected by a focus on present best practices, falling back on traceability and transparency and often only giving the public partial information.

You can purchase diamonds from Russia, but there’s no mention of how the revenues line the pockets of oligarchs.

Screenshot of Brilliant Earth’s website from summer 2018.

Canadian diamonds are offered as another alternative, yet there is no mention of ecological impact. You can read my 2009 RapNet article, on Diamond Mining Impact on People, Wildlife in NWT of Canada.

The “eco-friendly” Ekati mine in Canada—Wikimedia Commons

Another way diamonds get held up as ethical is through their tie to an Impact Benefit Agreement (IBA): “a formal contract outlining the impacts of the project, the commitment and responsibilities of both parties, and how the associated Aboriginal community will share in benefits of the operation through employment and economic development.”

However, large-scale mining requires very specialized knowledge, and local people lack those skills. Inevitably, they end up in low-paying, low-skill jobs—instead of being provided training that might benefit them in the future.

Additionally—for many Indigenous people, identity and land are completely intertwined. Decisions made by democratically-elected tribal councils can be at odds with traditional leadership structures that underlie cultural continuity. In fact, empowering the political elements of a tribe to exploit land and place (faced with the choice of jobs versus continual poverty) can be viewed as a final stage in the colonial destruction of Indigenous culture.

When the promises of mining companies are not met, and nothing of real value is gained, hope is lost.

The perspective of a large-scale mining company is diametrically opposed to many traditional Indigenous people, for whom the cultural identity, stories, history and ancestors are completely intertwined with the land from which they emerged.

While mines that offer engagements leading to IBAs are implementing best practices, the issues are complex.

Impact on The People

In 2011 I interviewed Mike Koostachin, a member of the Attwapiskat Cree Nation, which had an impact benefit agreement with De Beers. At that time, they were blockading the De Beers Victor diamond mine. Mike could not understand how his people could have so much wealth on their land, yet remain so poor.

Speaking of De Beers, he said, “They are the same regime, a modern-day regime. They have our tribal government. Instead of cutting off your arms and feet like they did in Africa, they are cutting off our land, our food from the land. The people are the land.”

In 2016, the Attwapiskat people were featured in the New York Times as the suicide capital of Canada.

(If only the Attawapiskat Cree had found a few investors, taken a small-scale approach, and run their own diamond mine—collaborating perhaps with technical and political advice from First Nations Women and Fair Mining Collaborative instead of DeBeers…)

Across the world lies Rio Tinto’s Argyle mine, located on aboriginal Australian land. Argyle is known particularly for its “champagne” (brown) diamonds, and its melee (diamonds less than 1/10 carat, typically used for accent).

This Vogue article discusses one designer’s use of Argyle diamonds: “The collection focuses on the ethical and social responsibility of sourcing diamonds. Each diamond is tracked from mine to market to honor its history and authenticity.”

In another version of the Argyle story, aboriginal spokesperson Ted Hall, former director and chair of the Traditional Owners Corporation, states, "You look at the impact of when royalty money started coming into the communities, that cash payment created a monster — that monster is greed and power."

His critique of the impact benefit agreement is similar to Koostachin’s: "Because it's a democratic system now: majority vote gets you into the council. We've had family members basically cutting each other off at the knee to get top doggy spot on the council, to control the council, to control the community, to control the wealth. He who holds the power ... benefits."

Recycled and Lab Grown Diamond Spin

Another option is recycled diamonds, which are touted as “eco-friendly.”

Screenshot from summer 2018.

What is never mentioned is that these diamonds could be blood diamonds—they are not transparently traceable to their original source.

Recycled diamonds have the same issues from an ethical point of view as recycled gold. They provide no support for small-scale miners, and they certainly do not stop any diamond mining company from digging into the ground.

Another option is lab-grown diamonds, which can simply be referred to as “diamonds.” While these don’t require as much energy as natural diamonds, their impact is still significant.

The ethical claims around diamonds from large-scale mining companies, recycled sources, and lab-grown companies bypass the fact that African countries need the economic gain possible through a supported diamond trade that could benefit the small-scale miner.

Here, I’m referring specifically to the 1.4 million small-scale diamond miners in the Central African Republic, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Ghana, and Tanzania who continue to work in poverty without regulation or oversight.

Small-scale diamond miners in Sierra Leone. Photo by Greg Valerio.

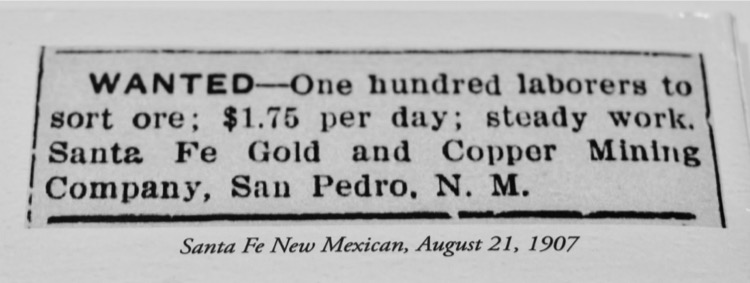

These small-scale diamond producers, whose communities were ravaged by war, are still making about two dollars a day—a quarter more than miners made back in 1907 just south of where I live.

One reason why the situation has not changed for these diamond miners is because ethical jewelers, including myself, focus on large-scale mining companies that provide traceability to source.

Large-scale mining companies support this traceability = ethical narrative approach, particularly the Canadian sector, which markets itself as conflict free.

As a result, there is no market incentive to deal with the small-scale mining issues, and the African miners continue to live marginally.

One last point—few jewelers who sell ethical diamonds will talk about the issue of polishing. Ninety percent of all diamond polishing occurs in Surat, India—where 100,000 children work as diamond polishers and cutters, and are tossed to the curb after their eyes go bad. An insider who knows the diamond business told me that 95% of Canadian stones are cut in India.

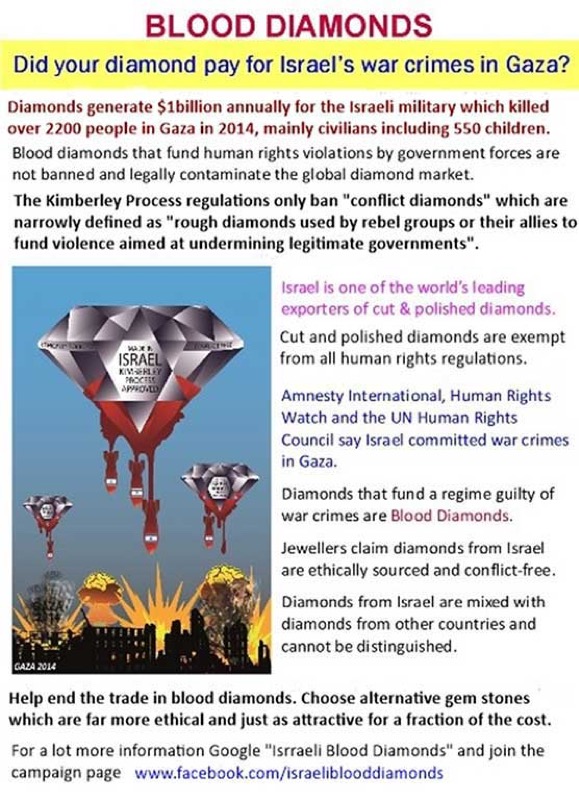

Another major hub for cutting is Israel. The connection between the Israeli diamond industry and its treatment of Palestinians has been broadly ignored by the jewelry trade and almost all ethical jewelers.

Image courtesy of Seán Clinton.

This concern has been a focus of Palestinian rights organization Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) for many years now. Seán Clinton leads this anti-Israeli blood diamonds campaign.

Beneficiation

Beneficiation is a term referring to creating as much downstream economy as possible in the community or country where mining takes place. For example, having diamonds polished and cut in the country where they are mined creates a tremendous number of local jobs.

It’s easy to simply export diamonds to an established cutting facility in Surat. What’s more difficult, and more expensive, is setting up these facilities near mines—because this involves equipment and training.

Botswana is the best example of a country that has benefitted hugely from having a controlling interest in mining within their own country. De Beers has a 50/50 joint venture with the government there. Botswana has set up polishing operations for their diamonds, which creates tremendous downstream economic benefit to local economies.

Botswana is often rightfully referenced as a successful example of a diamond economy benefitting economic development.

However, the De Beers/Botswana partnership does not absolve De Beers’ alleged complicity in conflict diamonds wars.

Let’s take a brief peek at Botswana as its own case study:

Sadique Kebonang, Botswana’s Minister of Mining, certainly seems to be reaching beyond his knowledge when he states, “I think it’s safe to say through the Kimberley Process we have seen the elimination of illicit diamond trading. As we stand, 99 per cent of the diamond that has been traded is free from illicit trading…”

Like nearly all people in the diamond sector, he denies the underbelly. Again, I reference this article in Foreign Policy, which details the black-market trading at around 30%, and the Kimberley Process certifications as easy to forge as an old driver’s license. Then, there is the ongoing Modi Scandal, which is rocking the entire Indian diamond industry, and the massive lab-grown diamond fraud that will plague the corrupt industry indefinitely.

Minister Kebonang ignores Kenneth Good’s concerns outlined in this article, The Social Consequences of Diamonds Dependency in Botswana. Quoting from page 1:

“Revenues from diamonds had been successfully directed into national and infrastructural development. But the over-concentration on diamonds led simultaneously to the nondiversification of the economy, the worsening of poverty and inequalities, and the continuance of ethnic discrimination and other forms of social injustice.”

The minister’s definition of “conflict free” does not apply to appropriation of Indigenous land. See: “Botswana government lies exposed as diamond mine opens on Bushman land.”

Kebonang’s pro-mining perspective seems to allow him to overlook the Indigenous humanity of those who get in his way.

In essence, there is no diamond equivalent to what is offered in Fairtrade Gold. No small-scale initiative that is independently accredited, where the People control the resources and benefit from the land outside of the grasp of large-scale mining interests.

Continue on to the Eighth Russian Doll: Brilliant Earth's Long, Tall Tale

Return to the Sixth Russian Doll: Kimberley Process' Damn Lies

Return to the Landing Page

**All writing and images are open source, under Creative Commons 3.0. Any reproduction of this material must back link to the landing page, here. For high resolution images for publication, contact us at expose(AT)reflectivejewelry.com.**