“There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know.” —Donald Rumsfeld

Ethical Jewelry Babble in a Russian Doll

The astonishing gap between what a diamond engagement ring or gold wedding ring represents and how it is sourced is a profound metaphor for disconnect in our times. To even consider it requires a kind of emotional fortitude, a deep stare into a funhouse mirror in which each pane reflects upon itself until you reach the center, the infinite depth of human brutality.

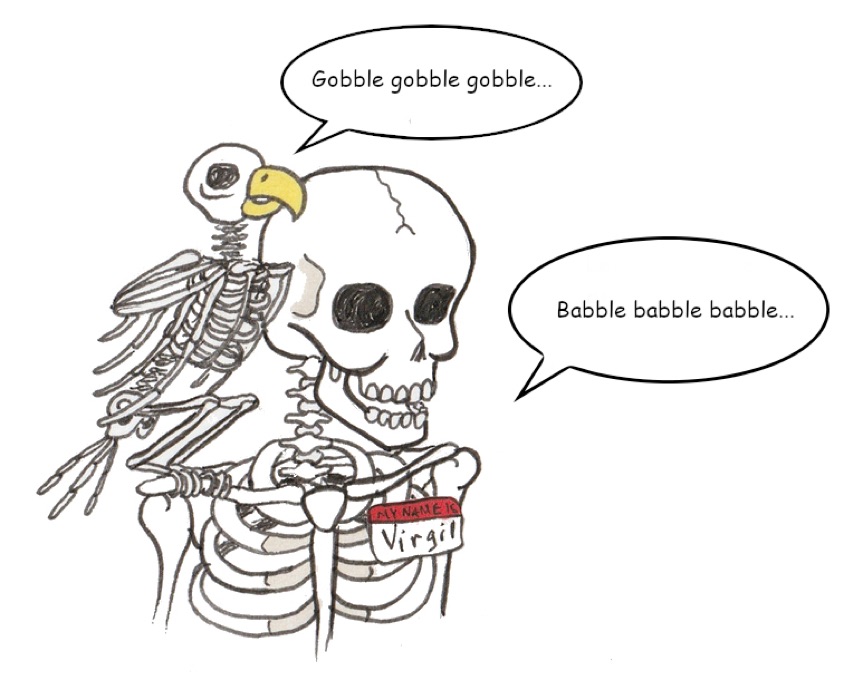

In order to structure the layers of deception, we will use as a central metaphor babble in a Russian nesting doll (aka a Matryoshka doll). There are nine layers in our Russian Doll exposé. To be precise: eight nesting dolls, and then the seed point at the center.

When you open this doll, each wooden figurine is beautifully seductive—and every layer tells its own story. You must open one after another to get to the smallest, tiny figure at the center.

The etymology of “babble” is associated with “babal,” a Hebrew word that means “to confuse.” Babble is the narrative that spins off and around the Tower of Babel, which was built in an attempt to reach the heavens, to become equal to God.

In our case, the objective in employing this babble to get everyone to speak their One Language: the fragmented bits and pieces of selected information which serves a consumer-facing narrative spinning dirty gold into “responsible gold,” or conflict diamonds into “conflict free diamonds”—a term which bypasses past human rights atrocities and is only “conflict free” in an absurdly narrow sense.

This is the alchemy of responsible jewelry marketing.

The One Language is backed up by certification systems, models for best practices, corporate sustainability reports, and detailed paperwork outlining chains of custody.

Sometimes it places initiatives for small-scale miners in the center of narratives—both trade- and consumer-focused. The strategy is a kind of bait and switch. Make minor initiatives—which are in themselves excellent—seem huge, when, in reality, they have little impact on the broader producer community. In North America in particular, such initiatives have no broad market impact.

Many jewelers, even the most progressive pioneers, support this One Language because they feel that, as one told me, “everything is basically going in the right direction.” From the One Language, the trade can broadcast positive stories—which are quite valuable. The “Diamonds Do Good” initiative found that consumers who read positive stories about the jewelry industry are 75% more likely to purchase a diamond.

In North America, the overarching unquestioned agreement among almost all jewelers, regardless of whether they are ethical pioneers or mainstream brick and mortar mall shops, is: we must present our trade as doing the best it can to address environmental and social issues. For the jewelry trade, this is a grand common-family agreement that is rarely trespassed.

To break with this narrative is an apostasy that few jewelers risk.

The First Russian Doll: Manufacturing Consent

Earlier this year, I received a high-end magazine entitled Beyond the Glass, which is sent to retailers from Stuller, the largest jewelry supply house in North America. Inside, it reads “The rising demand of sustainable sourcing in the jewelry industry and how Stuller can help.” In context to the history of the North American jewelry trade’s attention to these issues, it’s a major statement that would be unimaginable to me just a few years ago.

Image of Stuller’s Beyond the Glass catalog sent out to their customer base.

Stuller even has an Earth First product angle. Earth First! Now we’re talking! Oops, not to be confused with Earth First!

Anyway, here is a quote from their Earth First policy:

“Earth First symbolizes our ongoing environmental consciousness in manufacturing and our promise to act responsibly in all areas of business and production, including water, waste, energy management, safety, and the well-being of our associates.”

Again, nothing that focuses specifically on small-scale producers. They seem to be talking about policies in their manufacturing, not what is taking place at the mines where they source their raw materials. (Don’t get me wrong, a focus on green practices is commendable. But this absolutely should not be the exclusive focus of potentially powerful jewelry companies.)

The outermost layer of the Russian doll is made up of retail jewelers, trade magazines, and journalists and bloggers uttering their variations “responsible jewelry” around core messaging.

Part of my inspiration for wanting to write the Ethical Jewelry Exposé was the sheer volume of partial or misinformation—journalists, bloggers, and jewelers making claims that reminded me of the parable of the old blind men and the elephant.

Sorting out the agenda behind what appears is nearly impossible unless you have a deep and broad understanding of the issues related to sourcing.

This first Russian doll outlines some of the common themes in the interface between retail publications and leading jewelers defining marketing narratives that drive consumer behavior.

Washing Dishes for a Better World

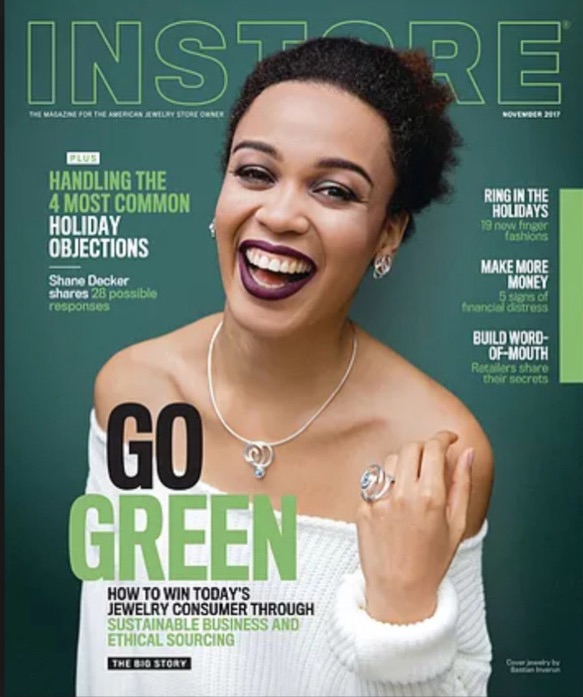

Ethical Sourcing was the cover story for the November, 2017 issue of Instore, one of the most influential trade magazines for jewelry retailers.

On page 45, we are told to, “Make sustainability, social responsibility, community support and responsible sourcing part of your brand promise, your marketing message, and every sales presentation.”

What exactly does that mean?

Unfortunately, the links to the articles, which were up in 2017, have been removed.

Open the issue and you’ll find three of the five articles focus on green building practices, including retrofitting lighting. This is a common theme I’ve seen across trade publications—a focus on green practices at home.

Then, there’s a special nod to an activity that jewelers can do to really make a difference:

Page 54, November 2017.

What’s striking is that small-scale mining and benefit to producer communities as a core issue in ethical sourcing is completely neglected.

Almost all the concerns, struggles, and challenges related to creating jewelry that would support the small-scale producer, the Pure Water People, get no ink.

In context to precious metals, “reclaimed” metals is the trade consensus.

In Stuller’s Beyond the Glass magazine referenced earlier, a jeweler who sells to Neiman Marcus also anchors “sustainable” recycled metals, “to deliver green jewelry to our customers.” Another savvy jeweler featured in the article proudly pushes recycled metals in their social media.

The Recycled Metals Story

The recycled metal narrative is arguably the foundation of the ethical jewelry story in North America, both for the trade itself and for the market.

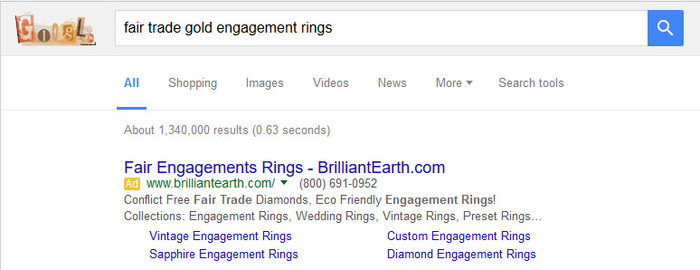

To a large degree, this is because Brilliant Earth (the Eighth Russian Doll: Brilliant Earth's Long, Tall Tale) dominates the ethical jewelry space in North America, with over a million visits per month to their website.

It seems like they are featured in just about any blog or article on ethical sourcing. They have defined recycled gold (or vintage) as the best possible choice.

I dispute BE’s claim above extensively in my article here.

But think about it. Do you believe a major multinational mining company such as Rio Tinto cares about how much recycled gold a jeweler uses? Gold is always going to be used for investment purposes—the accumulation of capital.

The impoverished small-scale gold mining sector, the largest contributor of global mercury contamination, which supplies about 20% of the world’s annual supply of gold, mines to survive. They do not care about your recycled gold wedding ring.

The origin of the recycled ethical gold story can be traced to 2007, when Hoover and Strong introduced it as a core element of their Harmony Line. This was a major breakthrough, a response to the No Dirty Gold campaign. I incorporated recycled gold into our jewelry and advocated for it.

Even today, recycled silver, though not particularly ethical in context to small-scale producers, is still best practice—because there are only minute amounts of Fairtrade Silver on the market.

However, once ethical Fairtrade/Fairmined Gold was introduced in 2011, recycled gold began to lose its validity as an ethical choice. Jewelers who wanted to be part of the solution recognized that the more ecological and socially responsible choice was to support small-scale miners’ best practices.

In the UK, the transition to Fairtrade Gold has changed the market. It’s anchored a change in consumer perception.

The January 2018 issue of UK’s Professional Jeweller listed Fairtrade Gold as a major trend of 2017, with over 200 jewelers selling Fairtrade Gold. “Fairtrade gold from Africa landed in the UK, and consumer press started to question the industry’s supply chain — with journalists discussing Fairtrade gold, lab grown diamonds, ethically-sourced stones and more.”

No jeweler in the UK would gain any traction by advocating for recycled gold ethics. But that is the story enforced over and over again by bloggers and journalists in North America.

Hoover and Strong, a family-owned company that has existed for over a hundred years, and the most ethical supplier in North America, started carrying Fairmined Gold in 2013 and today carries Fairtrade Gold—neither of which have gained traction in North America.

The reasons for the contrast between what is taking place in North America versus the UK are complex, and I detail them in the supplementary article, Fairtrade/Fairmined in the US/UK.

Fair Trade Spin

One of the most heinous trends is the specious use of the term “fair trade” or “fair-trade” in context to jewelry sourcing. The term “fair trade” has very positive connotations, which makes it an appealing phrase to use in the marketing of ethical fine jewelry.

Case in point: this recent article, entitled “India Posts Sharp Rise in Polished Exports in March,” published by IDEX, a leading insider trade magazine for the diamond sector.

In here, IDEX discusses the “four pillar principles of fair trade” in context to diamonds. The third principle is that a company “plays a dominant role in global diamond and jewelry advertising.” The last is “building state-of-the-art gemological laboratories.”

Of course, these two points have nothing to do with what we discussed elsewhere about the artisanal and small-scale mining diamond sector, or with the notion of fair trade as an initiative to help producer communities access the international market. The term “fair trade” is instead framed in context to corporate globalization.

(In context to fair trade and diamonds, this article in Foreign Policy Magazine documents the black market, fake Kimberley Process documents, and the child labor in Surat, India, where 90% of the world’s diamonds are cut and seized. Conflict diamonds are actioned off by the government and labeled as “conflict free”.)

Yet, in terms of retail narratives, even companies that sell recycled gold use the term “fair trade” in their marketing to create a positive image.

Same with fair trade diamonds. Fair trade diamonds do not exist—and yet, they are advertised.

Fairtrade is one of the most well-known global brands. There’s a good chance you recognize this logo:

Since April, 2015, I have been the only jeweler in the US that can use this logo with their product. In the UK, there are over 200 jewelers.

But many consumers do not know the difference between “Fairtrade Gold”—which is based upon a stringent certification from Fairtrade International—and “fair trade gold,” a term anyone can use.

The use of the term “fair trade gold” is particularly onerous in this context, because it creates market confusion and undermine the authentic Fairtrade Gold initiative, which benefits small-scale miners.

Ethical Diamonds Changing the World

Now a few examples of people who are breaking new ground…

DiCaprio is investing in and advocating for manufactured diamonds. Manufactured diamonds provide no benefit whatsoever for the small-scale diamond miners in the Blood Diamond film. In fact, they allow the market to bypass the real issues involved in supporting those communities—which DiCaprio has the economic power and influence to change. He could actually fund a fair trade diamond!

An article from Forbes features Brilliant Earth’s founder Beth Gerstein. The title of the article is, “Changing The World, One Diamond At Time.”

The Forbes article features a diamond-titled theme, but fails to give us any details of how BE’s supply chain from De Beers, Russian oligarchs’ Alrosa, or any of the other large mining sources is particularly changing the world in terms of how diamonds have always been sourced.

Certainly, these mines give communities work—but no control over the resources. Multinational mining exports profits for their shareholders. This practice stands in stark contrast to fair trade initiatives in which the people of the land control and benefit from the resources of the land.

Yet on their website, Brilliant Earth places their diamond sourcing in context to fair trade principles.

Screen shot, Brilliant Earth website. Taken summer 2018.

The illustrations pointed out here and in this entire section are indicative of how so much written about ethical jewelry in the US focuses on boosting up current supply chain practices, making them the “responsible jewelry” choice.

Yet behind all these narratives, jewelers have lined up behind one organization.

Instore Magazine (referenced in the beginning of this section) urges jewelers to ask suppliers if they belong to the Responsible Jewellery Council, to “crystalize your brand message and your social responsibility together” (p. 45).

The Responsible Jewellery Council is the organization that is relied upon for “responsible” standards and practices, and the subject of our next section.

Continue on to the Second Russian Doll: The Responsible Jewellery Council

Return to the Pure Water People Parable

Return to the Landing Page

**All writing and images are open source, under Creative Commons 3.0. Any reproduction of this material must back link to the landing page, here. For high resolution images for publication, contact us at expose(AT)reflectivejewelry.com.**